Lost Opportunity – the real tragedy of Indian Residential Schools

Can anger about the education a boy receives at 13 years of age motivate him politically into his late 80’s? I know it can. I knew John B. Tootoosis.

When John spoke about the residential school for Indian boys to which he was sent at 13 years of age, he did not talk so much about the physical, sexual and racial abuse many others have attested to in the Truth and Reconciliation hearings in Canada, between 2008 and 2015 (http://tinyurl.com/2ua5or2 ).

He spoke mainly of the lost opportunity. You see, John wanted to learn. He even wanted to learn from the Whiteman. But his school was more interested in having him do domestic chores, learn the Catholic Catechism and memorise reading texts in order to fool the government school inspectors into believing that he and the other students could read English fluently, when they couldn’t.

In 1982, John was 82 years of age. He went to England and Scotland to demand passionately that the British Parliament honour the promises Queen Victoria made to his grandfather’s generation on the Canadian prairies in 1876 when they signed Treaty 6.

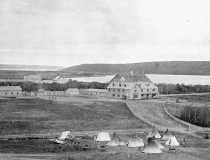

He carried with him to London the silver treaty medal the British had given to Poundmaker. John’s grandfather was Yellow Mud Blanket, Poundmaker’s brother. A few years after the treaty, the two brothers were imprisoned by the British general in charge of the Canadian militia and by the colonial court. Their crime? Organising a peaceful protest outside the gates of a British/Canadian fort in Battleford in modern day Saskatchewan. They wanted to discuss British breaches of the treaty. When the officials refused to talk, Poundmaker withdrew and led his people 55 kilometres west to Cut Knife Hill where they pitched their tipis.

That small community on the hill included women and children and the elderly. In this location, they were subject to a sneak attack by the British/Canadian military armed with cannons and a Gatling gun. The Indians suffered some losses, the military suffered more. Led by Poundmaker’s War Chief, Fine Day, they defended themselves successfully and drove the invaders away. This defensive action was classified by the military and the court as an act of treasonous rebellion, worthy of hanging, in some cases, and imprisonment in others.

The main breach of treaty the Indians wanted to discuss that day outside the gates of the fort, was the shortage of food that had reduced them to the point of near starvation. It had been brought about by the disappearance of the buffalo herds as a result of British settlement. This possibility had been foreseen by Poundmaker during treaty negotiations. He persuaded the British to promise that they would provide emergency rations in the event of famine and pestilence. But those rations were not forthcoming. In addition, the cattle and farm tools the British had promised to enable the Indians to develop an alternative economy were also not provided in the promised quantities or quality.

But a more enduring complaint over the century since has been the British and Canadian reluctance to provide schools for Indian children controlled by Indian communities, as promised in the treaty, and the consequent neglect of so many potentially brilliant Indian minds. John’s frustration at the lost opportunity for an adequate education drove him to develop a comprehensive political analysis. He campaigned all his life for aboriginal and treaty rights which would involve the recognition of Indian sovereignty and self-government within the Canadian confederation. In particular, he argued that the government-funded, church-administered residential schools should be replaced by Indian schools, and other educational institutions, which would be responsive to Indian communities. John has described all this in his own words as told to his daughter Jean Goodwill and her co-author Norma Sluman in his fascinating biography: Sluman, Norma and Goodwill, Jean Cuthand. John Tootoosis: Biography of a Cree Leader. Ottawa: Golden Dog Press, 1982.

Readers of my novel, Eaglechild, may have guessed by now that John was one of the inspirations for the fictional character, Clearvoice. I spent time with John B. Tootoosis in England and Scotland in 1981 and 1982, and other times in Canada before and since. I was honoured to be a guest in his home at the Poundmaker First Nation in Saskatchewan. At my request he spent time with my Indian, Métis and Inuit students in the University program I designed and directed in Alberta. He agreed, to serve on the board of directors of the Kanata Institute, which I founded. I write of John at greater length and more detail in my forthcoming non-fiction book, Nation to Nation – A memoir of the Canadian Indian constitutional campaign in London (1979-1982)

If you would like to be informed when that book and my other publications are released please sign up for that specific newsletter: ( http://bit.ly/1dRsQhH ) Meanwhile, here is a short excerpt from my novel about Cleavoice’s first day at residential school with his younger brother, Swimmer:

“Clearvoice lay in his bed, worrying about Swimmer, listening to the furtive last mutterings of boys in the dark and trying to understand his profound sense of unease. In his old age he would look back on that first night in residential school as the source of the realization that came to haunt him for the rest of his life – that he had become a stranger in his own land.”