Assimilation by Legislation – the realpolitik of Canada’s Indian policies before 1982

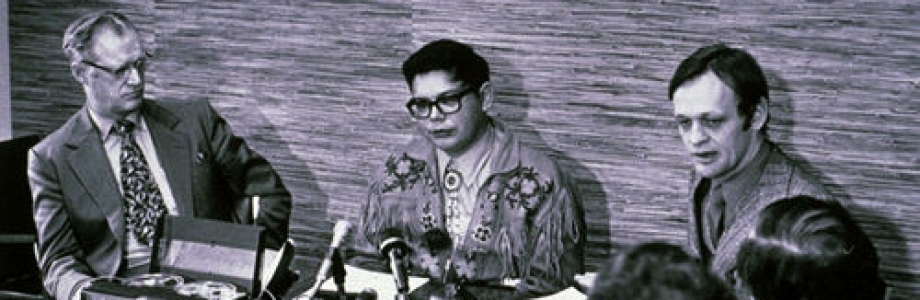

(The photograph shows Harold Cardinal, the young, intellectual Cree activist from Alberta, Canada in the early 1970’s. On his left is Jean Chretien who, in 1969, introduced to Parliament the White Paper on Indian Policy which essentially called for the assimilation of the Indian peoples and the extinguishment of their special constitutional status. Chretien was Minister of Indian Affairs, at the time, and was trying to carry out Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau’s vision for a society without treaties or aboriginal rights. He called it “The Just Society”. Harold Cardinal published two effective response – the first was called “The Unjust Society” and the second “The Red Paper”. Jean Chretien became Prime Minster in 1993.)

In my novel, Eaglechild, two characters, Ray Mackie, a cynical bureaucrat attached to the Canadian “embassy” and Percy Simpson, a British MI5 officer investigating the 1982 Indian constitutional campaign in London, discuss the difference between genocide and assimilation. Mackie speaks first:

“The way the Indians see it, it’s a never-ending story – get rid of the Indians – in a nice way, of course. Canadians are always nice.”

“That doesn’t sound very nice. It sounds awfully like genocide,” Simpson replied. “But genocide is quick, violent and illegal. Assimilation is slow and legal.”

“And nice,” Mackie added.

In London, no Indian organization used the word “genocide” to describe Canada’s Indian polices. That term implies a systematic program of physical extermination such as happened in Nazi Germany. Nothing like that happened in Canada.

However, the Indians did use the term “assimilation”. The realpolitik of Canada’s Indian policies had always been to get rid of the Indian nations as political entities with rights to territories and a special constitutional status within Canada. The method preferred by successive Canadian administrations was “assimilation by legislation”.

To understand the intensity of the London campaign pursued for three years between 1979 and 1982 by many Indian nations, one has to appreciate their existential fear that once Canada secured its formal political independence from Britain there would be no effective international restraint on this realpolitik.

Therefore, it was crucial that Britain observe the principles of its own Royal Proclamation 1763. It required that before there was any disposition of the land in Canada there should be agreement with the indigenous peoples arrived at in open meeting and approved by the Crown. Ominously, the Canadian government had locked Indians out of constitutional negotiations.

Some Indian nations had already reached historical agreements with Britain, and arguably with Canada, in the form of treaties which, in the words of the British, would last forever “as long as the sun shines, the grass grows and the rivers flow”. In the face of the UK Government’s claim that, as a practical matter, Britain could not continue to honour those treaties once Canada became politically independent in 1982, then the UK Parliament and Crown should ensure that Canada assume British responsibilities to observe the Royal Proclamation 1763 and the treaties forever.

That is the gist of the analysis I delivered to members of the UK Parliament and media in London in 1980-1982 on behalf of those several Indian nations who appointed me as their spokesman. I have reported this more fully in my memoir Nation to Nation.